E ka ʻohana Kamehameha, to celebrate and honor Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea, Restoration Day, we rejoice in the words and remembrances of our beloved Aliʻi Hawaiʻi and share some of the mea makamae (treasures) housed in repositories that care for our Hawaiian legacies and histories; the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum Library and Archives, the Hawaiian Historical Society, and the digital archives of the Papakilo Database and Ulukau.

Our founder, Ke Aliʻi Pauahi, was just eleven years old when Hawaiʻi’s sovereignty was usurped by the English Captain George Paulet in 1843. She recorded her own descriptions of the day Hawaiʻi’s sovereignty was restored six months later in her writing journal from the year 1843 while she was a student at the relatively newly-formed Chiefs’ Children’s School (Royal School), which had been founded by King Kamehameha III (Kauikeaouli) in 1839 for the purpose of educating the future leaders of Hawaiʻi.

Pauahi’s journal from her school years, one of the many treasures cared for by the Bishop Museum Archives, looks similar to those of students today; on its front and back covers, our princess proudly drew the hae Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian flag) and Kauikeaouli’s hae kalaunu (royal standard).

Pauahi had been learning to write in English for just a few years when she wrote the entry below (edits have been made to the original text for clarity and ease of reading and all changes are italicized). On this special Hawaiian national holiday, we are blessed to have our Princess’ own description of the day Hawaiʻi’s sovereignty was restored!

July 31 1843 Monday

“This day we…all rejoiced. It was raining this morning, we thought it was a bad day. After breakfast, Mr. Cooke told us we might go and get ready, so we did. At ten o’clock we went up to the plain. All the soldiers were there. We went into the house, and all the ladies were there. And by and by, Mr. Cooke came after Mrs. Cooke and Mrs. Judd to go up to the plain. We stayed there a long while. By and by, the King came with the Admiral on the wagon, I suppose. While we were there the soldiers fired their muskets. Afterwards, the boat fired with [a] 21-gun [salute] and the Craysfort, Dublin, Constellation & the Hazard and [on] Punchbowl Hill they all fired twenty-one guns.

Pretty soon they pulled down the English flag and hoisted the Hawaiian flag and we were all rejoicing. This evening the largest children went down to Mrs. Hooper’s and we sang, “God Save the King” and by and by Mr. Ball and Miss Fanny danced and we came home. – Courtesy of the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum Archives

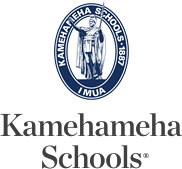

The mele “God Save the King,” mentioned by Pauahi inspired a new “Restoration Anthem,” composed by Edwin O. Hall and sung at the ceremony with the British Admiral Thomas, celebrating the restoration of the Hawaiian Kingdom on July 31, 1843.

The collection of the Hawaiian Historical Society includes the original handwritten lyrics of the “Restoration Anthem.” The digital repository of valuable Hawaiian newspaper articles, nupepa-hawaii.com, showed that the mele was published in the “Temperance Advocate and Seamen’s Friend,” just a day following its being penned for archival safekeeping by Hall on Aug. 2, 1843.

At the bottom of the lyrics page, Hall notes:

“Sung at the great cold water Luau given by H.H.M. Kamehameha III in Nuuanu to several thousands of native and all the Foreigners including the officers of 4 ships of war. For which Admiral Thomas thanked the Ladies & Gent who did him the honor. August 2, 1843.”

The newspaper article reads:

Restoration Anthem, 1843

The following hymn was sung by various circles on the day of the Restoration; as well as after the Temperance Picnic, given by His Majesty, to Foreign Residents and Naval Officers (English and American), at his Country Residence in Nuuanu Valley, August 3d.

RESTORATION ANTHEM.

Tune, ‘God Save the King.’

Hail! to our rightful King!

We joyful honors bring

This day to thee!

Long live your Majesty!

Long reign this dynasty!

And for posterity

The sceptre be!

Hail! to the worthy name!

Worthy his Country’s Fame

Thomas, the brave!

Long shall they virtues be,

Shrined in our memory

Who came to set us free,

Quick oe’r the wave!

Hail! to our Heavenly King!

To Thee our Thanks we bring,

Worthy of all;

Loud we thine honors raise!

Loud is our song of praise!

Smile on our future days,

Sovereign of all!

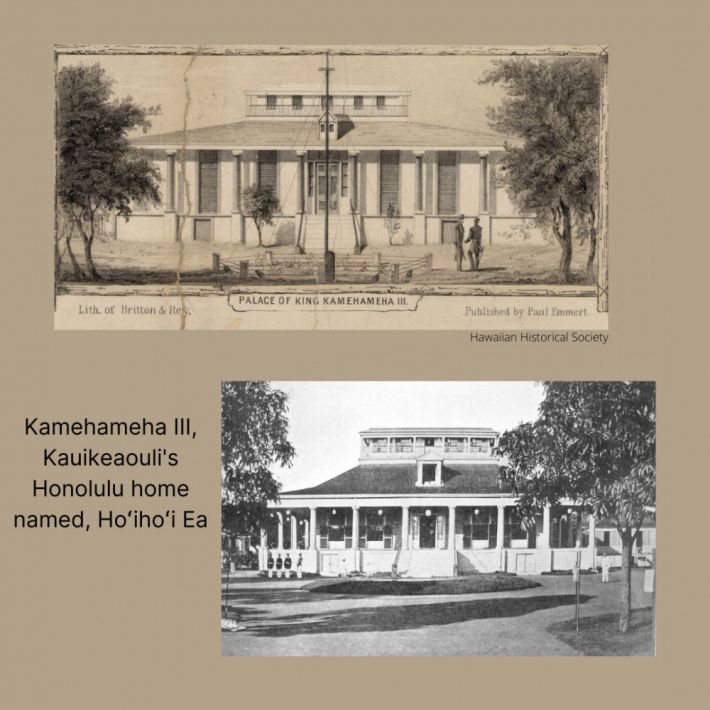

Also in the care of the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum Archives and the Hawaiian Historical Society are lithographs of drawings from renowned artist Paul Emmert’s most valuable series of historical architectural imagery titled, “Views of Honolulu.” Emmert’s six-piece collection provides the most complete visual record of the major buildings, residences, consulates and other structures in the years immediately following King Kamehameha III moving the capital of the Hawaiian Kingdom to Honolulu, Oʻahu.

Prior to the present day ʻIolani Palace being built, most of the Kamehameha line of aliʻi ruled the Hawaiian Kingdom from what was considered at the time, “the grandest home in Honolulu,” Hanailoia. Built in July 1844, the home was a gift to Princess Victoria Kamāmalu from her father, Mataio Kekūanāoʻa.

Kamehameha III purchased the home from his niece Kamāmalu when he officially moved his government from Lāhaina, Maui to Honolulu, Oʻahu in 1845. The King’s decision to move to Honolulu was entirely motivated by the experience of Paulet Affair. This was reflected in his decision to name the new royal residence, “Hoʻihoʻi Ke Ea” (“Restoring of Life”), named to commemorate the restoration of the Kingdom on Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea, July 31, 1843.

The original structure was very simple in design and was more of a stately home than a palace. It was constructed as a traditional aliʻi residence with only ceremonial spaces, no sleeping rooms. The residence had a throne room, a reception room, and a state dining room. Hoʻihoʻi Ke Ea was largely meant for receiving foreign dignitaries and state functions; hale pili (grass homes) used for sleeping and for retainers were preferred because they were cooler, and were built around the main building.

During the reign of Kamehameha IV (Alexander Liholiho), the palace building was renamed Hale Aliʻi meaning (House of the Chiefs). In 1863, during Lot Kapuāiwa, Kamehameha V's reign, it was changed to ʻIolani Palace in honor of one of his beloved brother Kamehameha IV's given names (Alexander Liholiho Keawenuiʻiolani); ʻIolani translates to “Royal Hawk.”

TAGS

hoʻokahua,kūkahekahe,cultural conversations,sovereignty restoration day

CATEGORIES

Kaipuolono Article, Regions, Themes, Culture, Community, Hawaii Newsroom, KS Hawaii Home, Kapalama Newsroom, Kapalama Home, Maui Newsroom, KS Maui Home, Newsroom, Campus Programs, Hawaii, Kapalama, Maui, Community Education, Department News

Print with photos

Print text only